Correlation between prediabetes, coronary artery calcification and cardiovascular risk factors: A 5-year retrospective case study

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.46475/aseanjr.v23i1.136Keywords:

Prediabetes, Coronary Artery Calcium Score, Framingham Risk ScoreAbstract

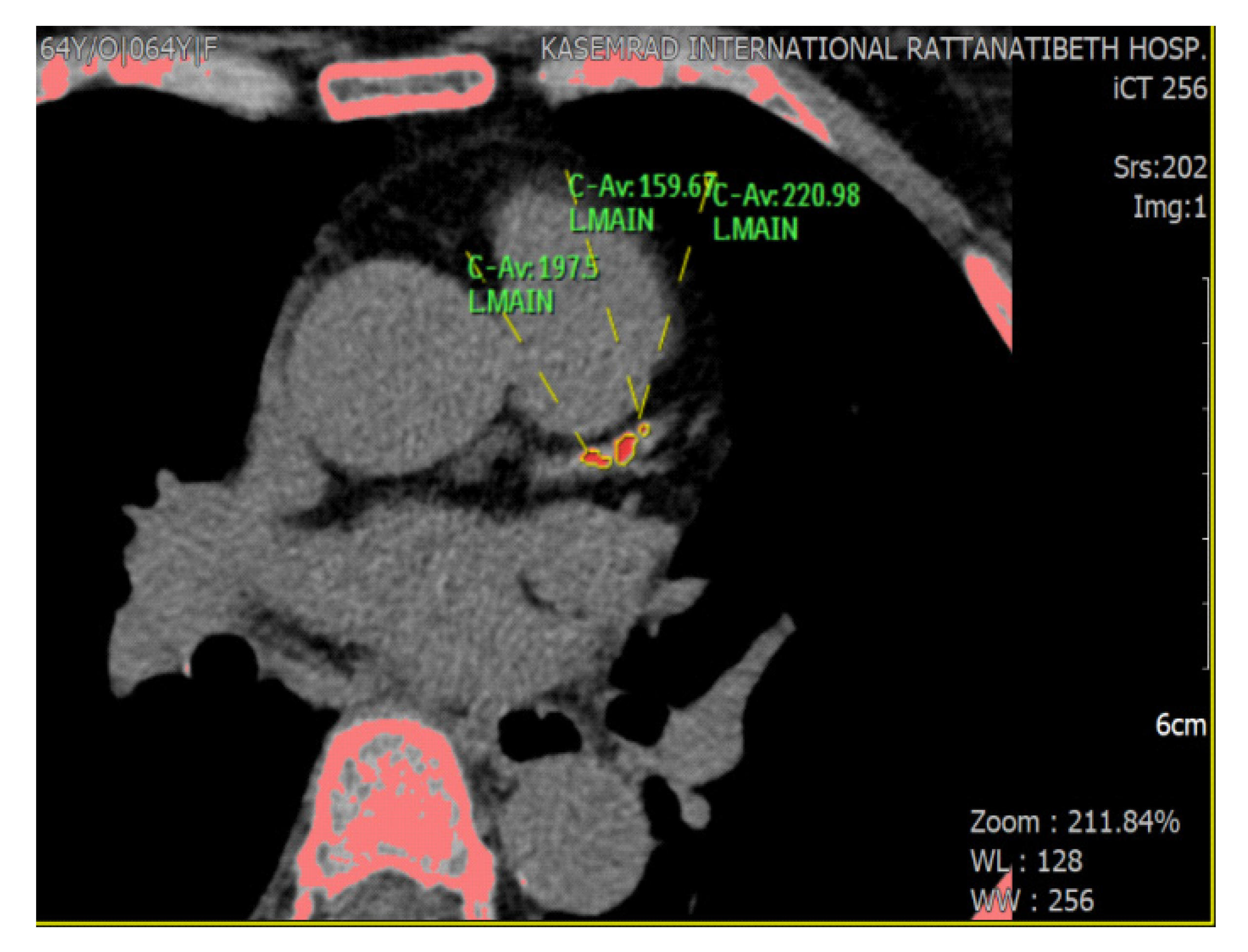

Objective was to evaluate the correlation between prediabetes, Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) 5.7 to 6.4%, cardiovascular risks (determined by Framingham Risk Score: FRS) and the coronary artery calcium score (CACS), by the retrospective analysis of 5 year data documents on PACS, Jan 2015 to Dec 2020.

Method: There were 1,639 eligible cases, reviewed by certified radiologists via Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS), with an asymptomatic condition in the check-up center, divided into two groups: - (1) the prediabetes group, with 756 cases and (2) the non-diabetes group, with 883 cases. The results of vital signs, BMI, CACS, blood test, HbA1c, fasting blood sugar (FBS), lipid profiles, and serum uric acid of all eligible cases were reviewed. Linear regression, t-test, chi-square, and Adjusted Odd ratio were used analyzed the significance and correlation between variables.

Results: (1) Most of the prediabetes participants (456 cases, 60.31%) had an intermediate risk of Framingham Risk Score (FRS). While most of the non-diabetes participants (665 cases, 75.31%) had a low risk of FRS., with a statistical difference (Chi-square, P < 0.05), (2) The prediabetes cases were significantly associated with coronary calcification at 2.38 times to the non-diabetic cases [Adjusted Odds Ratio = 2.38 [95% CI (1.98 – 14.98)]., (3) The intermediate cardiovascular risk (FRS) was associated with positive coronary artery calcification at 2.36 times to the low cardiovascular risk [Multivariate adjusted OR = 2.36 (95% CI (1.06 – 5.46)]., and (4) The high cardiovascular risk (FRS) was associated with positive coronary artery calcification at 8.64 times to the low cardiovascular risk [Multivariate adjusted OR = 8.64 (95% CI (2.65 – 18.58)]. Moreover, we found a significant higher serum uric acid in the prediabetes group than the non-diabetes group.

Conclusions: Subclinical prediabetes, among 47 to 62-year-old individuals, with an intermediate risk of FRS was significantly associated with positive coronary calcification (atherosclerosis). The combination of CACS screening with a safety low dose radiation protocol and FRS are of complementary together to evaluate the potential risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD). The benefits of combining CACS and FRS are used for decision making of the statin therapy, according to the ACC/AHA primary prevention guidelines (2019). Moreover, a high serum uric acid (UA) is a new challenging ASCVD risk factor in the present that we found it in prediabetes. The association of UA, cardiometabolic disease, and coronary atherosclerosis needs further studies.

Downloads

Metrics

References

American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017 Jan;40(Suppl 1): S11-S24. doi: 10.2337/dc17-S005.

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019;140: e596-e646. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678.

Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. Asia Pacific Symposium of SCCT [Internet]. 2022. [cited 2022 Apr 1]. Available from https://scct.org/events/EventDetails.aspx?id=1604244&group=

American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA). 2018 Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol Guideline [Internet]. Washington, DC: ACC/AHA [updated June 2019, cited 2022 Mar 1]. Available from: https://www.acc.org/~/media/Non-Clinical/Files-PDFs-Excel-MS-Word-etc/Guidelines/2018/Guidelines-Made-Simple-Tool-2018-Cholesterol.pdf

Nasir K, Shaw LJ, Budoff MJ, Ridker PM, Peña JM. Coronary artery calcium scanning should be used for primary prevention: pros and cons. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5:111-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.11.007.

Budoff MJ, Young R, Lopez VA, Kronmal RA, Nasir K, Blumenthal RS, et al. Progression of coronary calcium and incident coronary heart disease events: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61:1231-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.035.

Silverman MG, Blaha MJ, Krumholz HM, Budoff MJ, Blankstein R, Sibley CT, et al. Impact of coronary artery calcium on coronary heart disease events in individuals at the extremes of traditional risk factor burden: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J 2014; 35:2232-41. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht508.

Caliceti C, Calabria D, Roda A, Cicero AFG. Fructose intake, serum uric acid, and cardiometabolic disorders: a critical review. Nutrients 2017; 9:395. doi: 10.3390/nu9040395.

Borghi C. The role of uric acid in the development of cardiovascular disease. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31 Suppl 2:1-2. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1087985.

Higgins P, Dawson J, Lees KR, McArthur K, Quinn TJ, Walters MR. Xanthine oxidase inhibition for the treatment of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Ther 2012; 30:217-26. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2011.00277.x.

Stack AG, Hanley A, Casserly LF, Cronin CJ, Abdalla AA, Kiernan TJ, et al. Independent and conjoint associations of gout and hyperuricaemia with total and cardiovascular mortality. QJM 2013; 106:647-58. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hct083.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2022 The ASEAN Journal of Radiology

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Disclosure Forms and Copyright Agreements

All authors listed on the manuscript must complete both the electronic copyright agreement. (in the case of acceptance)